A study of deep learning methods for de-identification of clinical notes

We explored deep learning methods for de-identifying clinical notes across institutions, a crucial step in protecting patient privacy while enabling research on unstructured clinical text. Variability in data across institutions poses significant challenges to model performance. Our study tackles these challenges by introducing strategies to adapt advanced natural language processing (NLP) models to diverse institutional settings.

Model Architecture Overview

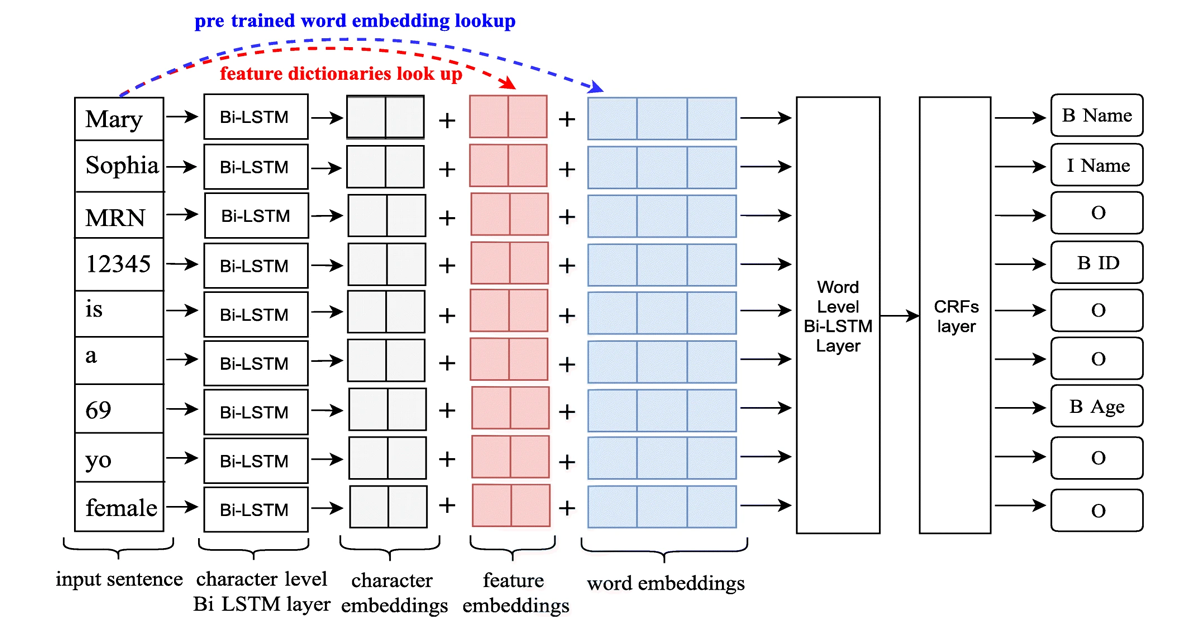

The core of our approach is a Long Short-Term Memory-Conditional Random Field (LSTM-CRFs) model, as illustrated in Figure 1. This architecture combines the strengths of:

- Character and Word Embeddings: Capturing semantic and contextual features of the text.

- Linguistic and Knowledge-Based Features: Incorporating domain-specific information such as part-of-speech tags, word shapes, and local vocabularies.

- CRF Output Layer: Enhancing sequence prediction to ensure valid PHI tagging.

This multi-faceted architecture enabled us to effectively capture the complexities of clinical notes and adapt to new datasets.

Key Features of the De-Identification Task

- The de-identification task involves more semantic categories compared to traditional clinical NLP tasks. It focuses on identifying sensitive patient information, such as names, phone numbers, and ID numbers, rather than medical concepts like diagnoses and medications.

- The primary goal of de-identification is to remove PHIs, making the identification of information more critical than determining its semantic category.

- De-identification systems use realistic surrogates to replace sensitive information for practical applications.

Data Preparation and Challenges

We used two datasets:

- i2b2/UTHealth Corpus: 1,304 clinical notes from 296 patients.

- UF Health Dataset: 4,996 clinical notes from 97 patients, spanning 39 note types. From this, we prepared 200 notes as the test set, 233 notes for training, and 77 notes for validation.

Key preprocessing steps included correcting typographic errors (e.g., missing spaces between words), sentence boundary detection, word tokenization, and BIO tagging schema.

Model Customization Strategies

We explored two strategies for customizing the i2b2-trained models for UF Health data:

- Merging Training Sets: Combined i2b2 and UF training sets to retrain the model from scratch.

- Fine-Tuning: Adapted pre-trained i2b2 models using UF training data. Fine-tuning proved more efficient, reducing training time and leveraging pre-trained parameters effectively.

Experimental Setup

Key parameters for our LSTM-CRFs model:

- Word embedding dimension: 300

- Character embedding dimension: 25

- Bidirectional word-level LSTM output: 100

- Bidirectional character-level LSTM output: 25

- Dropout probability: 0.5

- Learning rate: 0.005

- Gradient clipping range: [−5.0, 5.0]

- Momentum term: 0.9

- Training epochs: 30 (scratch), 15 (fine-tuning)

We evaluated models using micro-averaged strict and relax precision, recall, and F1-scores.

Results and Insights

- Fine-Tuning achieved the best performance with strict and relaxed F1 scores of 0.9288 and 0.9584, respectively.

- Adding linguistic features like word shape and part-of-speech, as well as knowledge-based features from local resources, further improved performance.

- Word embeddings from general English (e.g., CommonCrawl) outperformed embeddings trained on de-identified clinical text due to broader vocabulary coverage.

Conclusion

This study highlights the importance of adapting de-identification models for cross-institution settings. Fine-tuning, combined with linguistic and knowledge-based features, offers a practical approach to achieving robust performance. The insights gained from this work contribute to advancing privacy-preserving applications in clinical NLP.